NB: The below is a brief plain English summary of key points in the TAIC interim factual report. The Commission's report speaks for itself: taic.org.nz/inquiry/mo-2024-207

Briefly:

This report offers valuable lessons for the whole sector about making a good balance between traditional navigation techniques supported by appropriate use of electronic instruments. Safe navigation means choosing techniques that fit the conditions. And routine conditions are where habits form, but unusual conditions are where they’re tested.

What happened

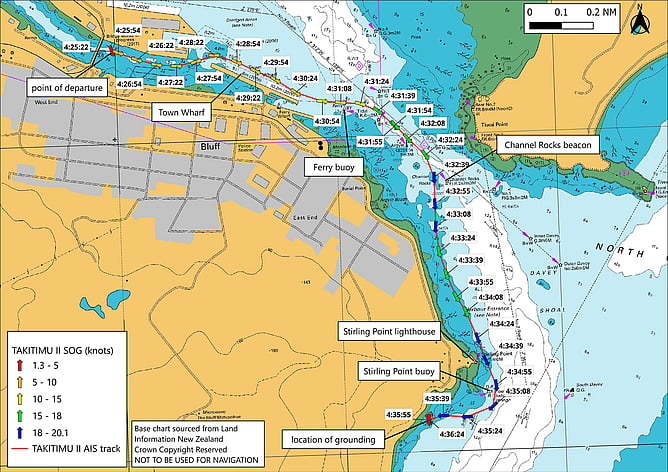

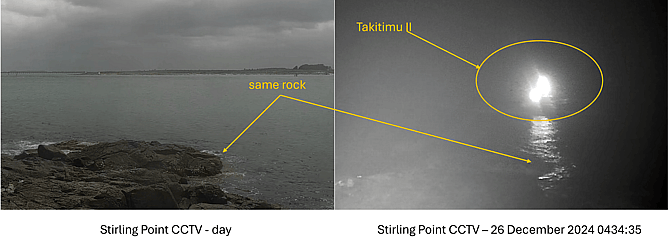

In December 2024, South Port’s pilot boat Takitimu II set out from Bluff to transfer a pilot to an incoming ship. After passing Stirling Point the master made an excessive course alteration and at about 18–20 kt the vessel ran aground on rocks and sustained moderate damage to its hull and underwater fixtures. Two of the three people on board suffered minor injuries. There was no pollution. Coastguard later towed the vessel off the rocks and back to port.

Why it happened

Speed and route choice reduced the time available to detect and correct course. Fog patches in the area restricted visibility, yet the master navigated by referring to their usual visual references and didn’t make effective use of the compass and electronic navigation equipment. The deckhand alerted the master when navigation screens showed they were heading toward shore, but by then there was insufficient sea room to avoid the rocks.

(The Commission found that no mechanical fault, medical event or distraction contributed to the accident.)

Safety issues and Recommendations

TAIC identified two linked safety points:

Electronic navigation tools provide a more reliable cross-check when visual cues are degraded. In lower visibility, navigating mainly by eye limits a master’s ability to confirm location and heading.

When tasks are done repeatedly without incident, techniques that work ‘most of the time’ can get normalised, even when people know they’re risky in challenging conditions. This is a common risk in safety-critical operations. At the time of this accident, South Port’s Maritime Transport Operator Plan didn’t require periodic verification of navigation proficiency of pilot-vessel masters. The port had no formal way to confirm that everyday navigation practices continued to reflect best practice.

There was no need for the Commission to make a recommendation. South Port has updated its training and procedures, added six-monthly proficiency assessments and revised its MTOP and standard operating procedures.

Reminders for marine operators

This report serves to remind marine professionals:

Use all available navigation aids to confirm position and monitor progress, especially when visibility is reduced.

Make it a habit to cross-check between visual cues and electronic instruments in departure and passage checklists.

Set safe speeds that allow time and sea room to detect and correct errors.

Standardise routes and passage plans and include them in SOPs.

Implement regular, documented proficiency checks and refresher training for launch and pilot-vessel masters.

No repeat accidents – ever!

The principal purpose of the Transport Accident Investigation Commission is to determine the circumstances and causes of aviation, marine, and rail accidents and incidents with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future, rather than to ascribe blame to any person. TAIC opens an inquiry when it believes the reported circumstances of an accident or incident have - or are likely to have - significant implications for transport safety, or when the inquiry may allow the Commission to make findings or recommendations to improve transport safety.